(Other than some very brief details, there are no plot spoilers for Alan Wake 2 or for any other game in this post, though gameplay mechanics of Alan Wake 2, Return of the Obra Dinn, Outer Wilds, Condemned 2: Bloodshot and A Hand with Many Fingers are discussed)

In my last post, full of praise for Alan Wake 2, I briefly mentioned that the Mind Place ‘detective sim’ system that is part of Saga Anderson’s story doesn’t really work as a simulation of the mental process of undergoing a detective investigation, and I think its worthwhile to explore why.

(Also my last few blog posts have been almost exclusively about writing in games so it’s nice to actually explore mechanics and systems instead)

As an FBI detective, Saga Anderson has access to a ‘Mind Place’, her version of the so-called Mind Palace cognitive technique, where a person organizes and stores memories and information within a physical environment they conjure within their mind. As part of her Mind Place, Saga Anderson has a case board where she organizes the various pieces of evidence she collects and attempts to make new inroads into the case she is investigating.

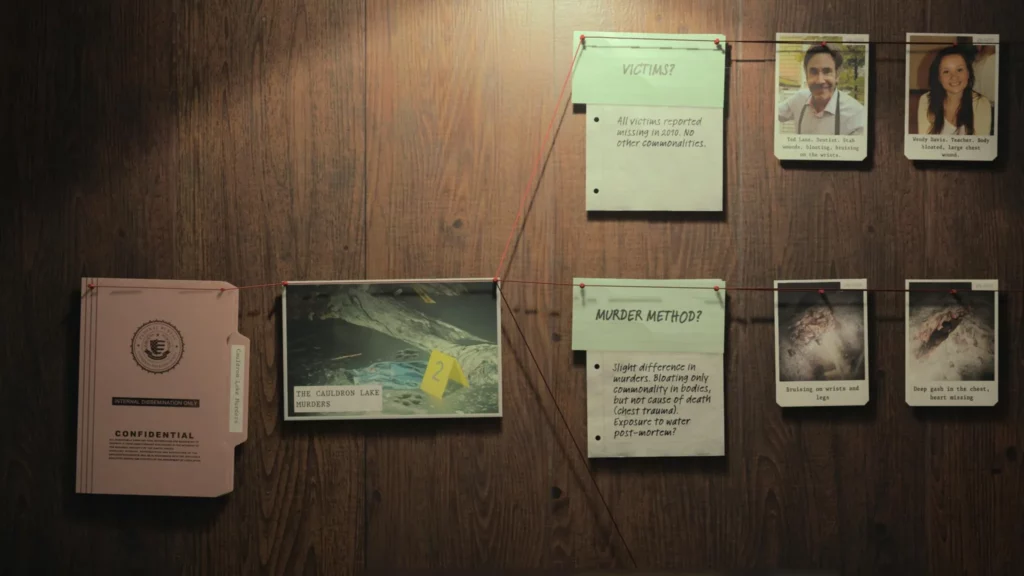

This is how it works in practice: in her travels around the town of Bright Falls and the surrounding areas, she will discover, locations, markings, and so forth; objects that serve as clues to the overarching mystery. Polaroid photographs of these evidences are then generated within her Mind Place. As the mystery progresses, the case board in her Mind Place will begin filling with index cards with questions pertaining to the mystery, such as ‘who are the member of the cult?’, ‘what are the goals of the cult?’ or ‘what symbols do the cult use?’. The player must then sort through the gathered evidence and assign them to the relevant questions. Once sufficient evidence is assigned to a question, Anderson automatically makes a logical deduction from said evidence and the question is considered answered. This could then lead to further questions, or new sub-cases, and the cycle repeats.

As a simulation of the ‘detective experience’, it’s rather lackluster. At best, this system simulates the rote procedural aspects of conducting an investigation, but leaves the interesting aspects of it entirely out of the hands of the player. To understand why this is so, we have to understand what investigating looks like. Broadly speaking, the process of investigation can be divided into 3 phases:

- The acquisition of information

- The organization of acquired information

- The synthesis of new information from the acquired and organized information

In Alan Wake 2, the acquisition of information largely happens on its own as players progress through the game’s story and triggers specific plot beats. Ultimately, the game wants you to progress, and the story its telling is largely linear, so there is little room for the player to ‘fail’ in acquiring critical evidence or to gather evidence in a non-linear fashion. If the game must guarantee that players acquire evidence so that the game can progress, and evidence is gathered in a strictly linear fashion due to the story’s linearity, then there is little challenge or variance to this information gathering process. There is no need for players to be perceptive of the environment or to translate physical evidence into quantifiable information or to filter relevant information from the irrelevant.

The argument could be made that making the acquisition of information into a compelling and engaging process for the player would require that the game be largely open world or non-linear in some fashion, and indeed some of the best investigative mystery games are open world to some degree. The incredible and excellent game Outer Wilds is fully open world, and the process of uncovering clues to the answer to the game’s central mystery is the game’s core hook, and it’s an incredibly compelling one at that. A treasure trove of breadcrumbs lead in various directions and unraveling them all requires creative combinations of logic and lateral thinking. It’s open world nature means if players are ever stuck, they can spend time chasing down other leads while ruminating on the one they are stuck on. Information gathering in Outer Wilds is compelling enough that the designers decided that organizing the information you gather is largely uninteresting in comparison, so Outer Wilds’ equivalent of Alan Wake 2’s case board, the ship log, automatically records and organizes the information you gather without intervention from you.

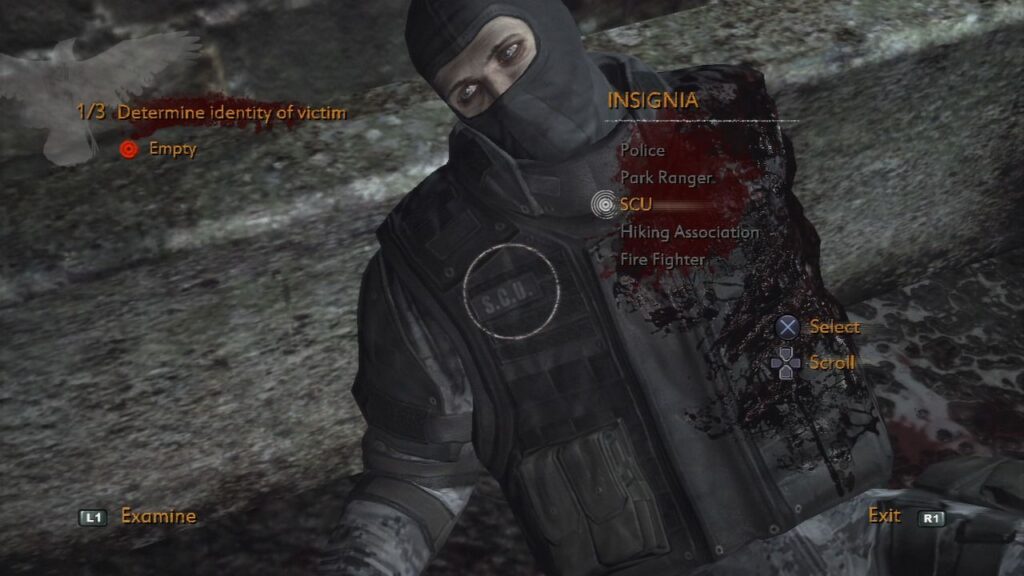

However, I don’t think an open world is necessarily a prerequisite to making evidence gathering an interesting process. The first person horror ‘brawler’ game Condemned 2: Bloodshot features a forensics system where at key points in its linear story, players must examine a crime scene in detail and using their own observational skills, answer key questions (accomplished by choosing the correct answer from multiple choices) about the crime scene. It’s still not as interesting as the investigatory experience in something like Outer Wilds as you don’t get to make larger logical deductions concerning the case outside of these individual crime scenes, but the moment to moment gameplay of observing these ghastly and horrific scenes and combing them for details is quite compelling and I can’t help but feel Alan Wake 2 would have benefitted from something similar.

As mentioned, Alan Wake 2 focuses its efforts on simulating the second phase of the investigation process, the organization of acquired information. However, this is perhaps the least interesting phase of an investigation as a lot of it is largely rote work of dividing evidence into separate categories/questions. In fact, what is perhaps the most interesting aspect of this phase, deciding what these categories should be to begin with, is handled entirely by the game, so in effect all that is left for the player is dropping the correct evidence into the correct category, effectively a glorified version of the classic children’s game of dropping shaped blocks into the corresponding slots of a bucket.

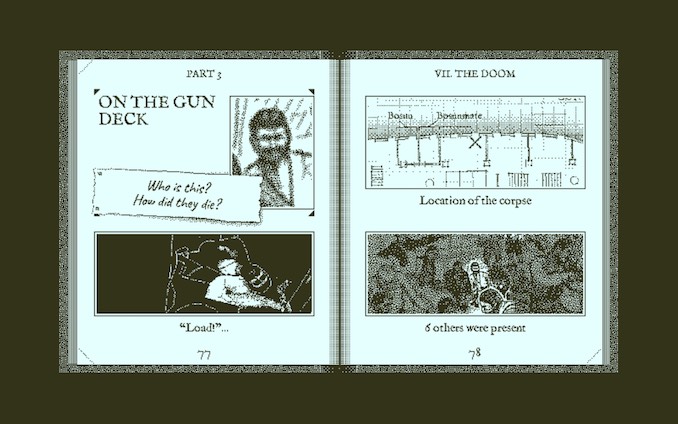

The brilliant mystery game Return of the Obra Dinn also assists players in organizing information (in Obra Dinn’s case, the names and causes of death of the various passengers and crew aboard the titular ship) by providing them with a notebook with a list of names of passengers and crew and various possible causes of death. Players can then tag photos of people with their names and causes of death as they explore the ship, much like assigning evidence to questions in Alan Wake 2. However, in Obra Dinn this information is not validated as correct immediately – validation only happens when 3 passengers/crew are correctly named and their fates ascertained – so players are left with some uncertainty and are also given some freedom in reassigning fates and names if new evidence seemingly contradicts old ones. Organization of information becomes intertwined with the other phases of the investigation process, and the uncertainty of the correctness of the player’s organization of information reflects the uncertainty of the player’s logical conclusions. This doesn’t happen in Alan Wake 2 as assigning evidence is always immediately confirmed as correct or not. It seems possible that taking a similar approach to Obra Dinn, i.e not validating assigned evidence immediately but perhaps waiting for a certain threshold or key future plot beats to occur, could introduce ambiguity and uncertainty that makes players more attentive to the specifics of the evidence they are gathering (or maybe it will just confuse the player!).

Another possible approach to making this phase of the investigation more interesting is to give players the tools to organize information and to let them go wild, so to speak. In the indie investigative thriller A Hand With Many Fingers, players play a researcher delving into the archives of the CIA looking for information on a Cold War conspiracy (an actual real world conspiracy in fact!). Alongside the endless rows of shelves containing the government’s many secrets is a reading room with two cork boards. As players trawl through the archives and uncover file photos, newspaper clippings, call transcripts and other forms of evidence, they can pin these documents up onto the cork board and connect them to each other with red string, creating a complex web of connected information not far off from the case board in Anderson’s Mind Place. The key difference here is that the game does not organize any of the information for you at all. You are free to pin or not pin any documents however you like, wherever you like, and you are free to connect them up in any manner. The challenge of organizing, categorizing, and connecting the evidence is left entirely up to you and as the mystery unravels further and more and more documents are uncovered, your personalized case board will invariably grow more and more complex and disorganized. As intriguing as this free form system is, transplanting it wholesale into Alan Wake 2 is unlikely to work, but I cannot help but wonder if a modified version of this could still work, where players are free to connect information as they see fit but must connect certain pieces of information together in specific ways so as to unlock a logical deduction necessary to progress the story.

The last phase of the investigation process, the synthesis of new information from existing information, i.e the process of logical deduction, is the hardest to simulate and most games simply leave it to the player to perform this in their own heads. How do you systemically simulate intuition, or logical inference? There are countless conclusions and logical leaps a person could make from a given set of clues and countless means of achieving the same conclusion, so the number of permutations of possible deductions a game must represent is considerable. Even if the permutations are pared down, simulating logical deductions step by step in the game may risk making the player feel condescended to from being fed unnecessary breadcrumbs and the moment of epiphany may be robbed from them by making the answer needlessly obvious. Instead, games typically focus on validating if the player’s deductions are correct. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, Return of the Obra Dinn does little to guide you through the process of deducing who is who and how they died. Instead it only validates if your inferences are correct by marking correct names and causes of death (in groups of three as previously mentioned) as such when entered correctly. The game remains incredibly engaging even though so much of it happens in your head.

A Hand with Many Fingers doesn’t even go that far. The game unravels and progresses as you find new evidence in the archives. It does not test if you understood the evidence or not. The only requirement to progress is finding the right keywords to search in the archives by reading existing clues. However, the game assumes that you are interested in its central mystery by virtue of the fact that you are playing the game, and so you’d naturally reconstruct the timeline of its central conspiracy as you uncover the evidence, even if the game doesn’t really require it.

Alan Wake 2 does neither. Once sufficient pieces of evidence are gathered and correctly assigned, Saga Anderson the character makes the logical deduction on her own in a short cutscene, without any player intervention required. No thought or logic or intuition is necessary from the player at all. If information gathering is largely linear, and logical deduction is largely automated, then all that’s left is the rote categorization of information, and while this may be interesting and novel for a short while, it quickly becomes apparent that the case board system is paper thin and merely emulates the appearance of conducting an investigation, without any of the real legwork (or brainwork) involved. I’m disappointed by it as it’s quite the missed opportunity in an otherwise excellent and groundbreaking videogame, and even just a few improvements to it would have dramatically improved it and its contribution to the overall tone and atmosphere of a game already oozing with tone and atmosphere. As an intellectual exercise, here’s some suggestions on how to improve the investigatory mechanics in Alan Wake 2, taking inspiration from the other games mentioned:

For one, have players examine environments and props carefully to unlock clues rather than have it done automatically. The game could require players carefully examine and point out specific cues in an environment that are noteworthy in order to unlock the clue. Rather than have Anderson spell it out through voiceover as the game does now, simply have her say something like “hmm, there’s something strange here” as a prompt for the player to investigate further. Introduce some amount of logical deduction by requiring players answer some basic questions about the highlighted environmental cue like in Condemned 2: Bloodshot. For example, in the autopsy scene early in the game, players could be prompted with questions like ‘how many times was the victim stabbed?’ or ‘what is the cause of death?’ and players must answer these questions by paying careful attention to the corpse. As a fallback, should the player fail, Anderson the character can answer correctly for them, but players may lose out potential rewards as a consequence.

Secondly, allow players to freely assign evidence to questions on the case board without immediately rejecting them if incorrect. If a certain number of evidences are assigned incorrectly to the question, remove all incorrect evidence from the question at once. Also, allow players to freely move the questions and connected evidence around the physical space of the case board to their heart’s desire.

Thirdly, don’t have Anderson the character automatically make the logical deduction that answers the question on the case board. Instead, let players assign possible answers to each question, but do not validate the answer immediately, instead treating it as a hypothesis in the meantime. Once a certain threshold of evidence is acquired and correctly assigned, some possible answers are eliminated as they contradict the evidence. Players can then attempt to choose the correct answer from the remaining options, and are rewarded if they choose correctly. If they don’t, Anderson answers correctly on their behalf.

These three changes aren’t minor per se, but they aren’t major enough to require extensive changes to the rest of the game, its story or overall structure. Nevertheless, they could introduce some amount of challenge to all three phases of the investigatory process, requiring some level of logical deduction and intuition from the player. These changes wouldn’t make Alan Wake 2 the most amazing and engrossing detective game out there, but that’s fine. That’s not what the game is aiming to be anyway. What they can achieve is adding some mental challenges for the player; challenges that put the player in the right mood and frame of mind, that of a detective on an intriguing and challenging case. Alan Wake 2 is already is a masterpiece of mood, these changes would simply let the mechanics reflect and enhance the mood.