In the previous blog post I discussed why dismissing AI Art completely (rather than critiquing the structural economics) is a misguided perspective. There is, however, a more fundamental reason why I believe this: I think this is a fight that artists will inevitably lose.

(I know, finally, a REAL hot take.)

Assume, as I think most artists do, that AI art poses a real economic danger to the livelihoods of artists (the fact that artists care so much about this already implies this). What are the means and methods by which artists can prevent this? You can maybe create a social climate in which making or using AI art is socially unacceptable. You can also negotiate employment and freelancing contracts that prohibit AI art. You can even go further, assuming some utopian government, mandate a nationwide ban on AI art.

While these may slow down the development and proliferation of AI art, I’m not sure this will eliminate it or even prevent its future flourishing. AI art, or AI in general, is a form of technology, and I think most, if not all, forms of new technology follow what I think of as a ‘Pandora’s Box’ principle: once the knowledge of this new form of technology has been made public, it is fundamentally impossible to stop its growth and development if the technology provides some form of practical benefit to a nation, corporation, or individual.

This principle is a consequence of the nature of technology and the international economic order. Namely, there are 3 main factors:

1. Most technologies are not hardware-constrained

Most new technologies these days are not hardware-constrained, that is, these technologies do not require unique, expensive or generally hard to acquire hardware resources in order to utilize them. These technologies typically come in form of software that can run on a wide range of computing hardware. The ‘soft’ nature of these technologies means they are intrinsically duplicatable and can be easily transmitted over communication networks.

In the 90s, the statement on this t-shirt would have been true. Under US Federal law then, cryptographic systems using keys longer than 40 bits would have been considered ‘munitions’ and exporting them outside of the US would have been a federal crime. This law was ostensibly meant to allow the the US government to retain the ability to decrypt intercepted messages sent by hostile foreign governments and entities, but as implied by the existence of this t-shirt, did little to actually stop the transmission of these ‘illegal’ cryptographic systems. After all, these systems are essentially algorithms, easily encoded as text and transmissible over a wide variety of mediums, including t-shirts! Given a specification, pseudocode or actual source code, any programmer can implement the algorithm in various programming languages for various hardware and software platforms. Even with federal laws against the transmission of these algorithms, all you need is a single ‘leak’ and now cutting-edge cryptography belongs to everyone.

In fact, all this law did was punish ‘legitimate’ companies like web browser developers who were forced to use inferior and insecure forms of encryption in order to comply with the law, thereby exposing innocent users to potential intrusions from cybercriminals.

Cryptography isn’t alone in featuring this ease of transmission. Peer-to-peer file sharing is similarly transmissible. Here’s the specification for the BitTorrent protocol in a single webpage. Blockchain is another one. The Ethereum Yellow Paper defines all the information you need to build a Ethereum client. Want to deploy your own NFT? Here’s the original specification for it. These technologies can’t even be reduced to specific software applications. The applications in question are just implementations of the technology. The technology is an idea.

2. Hardware-constrained, but with fungible hardware

Of course, not all new technologies are free of hardware constraints. AI art models do have hardware constraints. While the models themselves are composed of billions of numerical weights that can be transmitted fairly easily, training these models relies on a fair amount of computing resources, typically graphics processors from manufacturers like Nvidia.

However, even these hardware constraints aren’t massive hurdles hindering the proliferation of these technologies. AI models, along with some other technologies, have hardware constraints but the hardware resources required here are largely fungible, i.e. they aren’t unique and irreplaceable. Nvidia GPUs aren’t fundamentally different from GPUs from other manufacturers. They may be more cost-efficient and more powerful, but GPUs are GPUs. If the US wanted to maintain a choke-hold on the development of AI and restricted the export of Nvidia GPUs to foreign nations, these foreign nations will simply find an alternative supplier of GPUs or may simply manufacture their own. An individual nation can be protectionist, authoritarian or socialist all they like but in the international paradigm, capitalism and the markets rule above all.

Another example of fungible hardware constraints is 3D printed firearms, or 3D printing in general. The 3D models for such firearms are easily transmissible, but they do rely on 3D printers, but 3D printers aren’t special either. Fundamentally, they operate on identical principles and they are widely available from various manufacturers based in various countries. It’s easier to restrict the dissemination of the ‘fire’ in firearms, i.e. ammunition and gunpowder, than to restrict the design and printing of the firearms.

3. Hardware-constrained with non-fungible hardware

We’ve already established that AI models don’t have any unique hardware constraints that might be a means of controlling its development, but not all technologies are similarly blessed. Some technologies fundamentally require unique resources or hardware that are difficult, expensive or downright impossible to replicate. However, the development of these technologies, slow as they are, continue largely unabated. Quantum computers and nuclear weapons are good examples. They both have very unique and non-fungible hardware and resource constraints (okay uranium is technically fungible, but it’s rare enough that it practically isn’t), yet we still see development in these technologies. Even nuclear weapons, universally agreed to be awful things, are still being developed by some nations like North Korea.

The reason for this is simple: if a nation has an economic or political incentive to further develop a technology, then they will do so, even if it involves going out of their way to procure or manufacture the unique resources or hardware needed. If a hostile foreign nation chooses to ban said technology or to cease development of it, then there’s even more incentive, as the technology presents an opportunity to achieve some form of superiority over the foreign adversary.

This reasoning ‘trickles down’ to individuals and corporations too. If a given nation chooses to restrict or ban a particular technology, then foreign nations friendly to such technology presents an opportunity for a geographical/jurisdictional arbitrage: move yourself, or your business, into the domicile of a nation that is friendly to the work that you are doing. Is the US hostile to cryptocurrencies? Well, move to the UK, who is much friendlier. They might even dangle incentives for you to make the move.

This ‘arbitrage’ happens on a cultural level too. In my last blog post, I gave an example of AI Art created by Varun Gupta, who is from India. This was not a random choice. Sentiments on new technologies tend to be heavily divided along cultural/geographical lines. According to a 2021 Ipsos survey, “Citizens from emerging countries are significantly more likely than those from more economically developed countries… to have a positive outlook on the impact of AI-powered products and services in their life”. For artists in developed nations, AI art is a threat to their livelihoods, for those in developing nations, its an opportunity to improve their livelihoods, so what reason would they have for wanting to ban it?

Inevitable

To summarize, any useful technology will inevitably be adopted as most technologies are not hardware-constrained, making them easily to duplicate. When they are hardware-constrained, they are typically constrained with common and fungible hardware that can be easily manufactured or procured. However, if the technology is in fact hardware-constrained by rare and non-fungible hardware, then economic and political incentives means that someone, somewhere, will work on developing and utilizing the technology anyway even if some societies choose to ban it.

Let’s return to the discussion of AI art, or AI in general. Assume the US and other western nation do, magically, somehow decide to ban the use of AI for the production of art and media. Do you believe that foreign nations will somehow follow suit? In a multi-polar world where foreign perception of the US and the west is increasingly ambivalent at best, will foreign nations and their people not instead leverage this opportunity? A global superpower has just decided to cede this technological throne, and it is now ripe for the taking. Why not invest even more in AI? Develop local media industrial complexes through AI, either becoming new outsourcing centers for American media corporations or heck, supplant them entirely.

If AI will inevitably win, then fighting back is not necessarily of greatest importance. Maybe that buys you some much-needed time, but it still evades the fundamental question: When AI wins, who will be its allies? If you choose to dismiss AI and consider it anathema, then you might be leaving room for artists who are not so resistant to its allure to become AI’s allies, and it will be them who sit alongside AI at the victor’s side of the negotiation table.

Yes, this is a very doomer accelerationist take! Yet I’m not so sure I’m wrong here. The history of humanity is a history of relentless technological adoption as long as the costs of said technology can be externalized, and in the case of AI, externalizing the costs to artists is incredibly easy. Short of overthrowing capitalism, AI’s victory might be inevitable, and the best we can hope for is to tweak this outcome to our benefit, whether with regulation or new social contracts with governments, corporations and individuals in society.

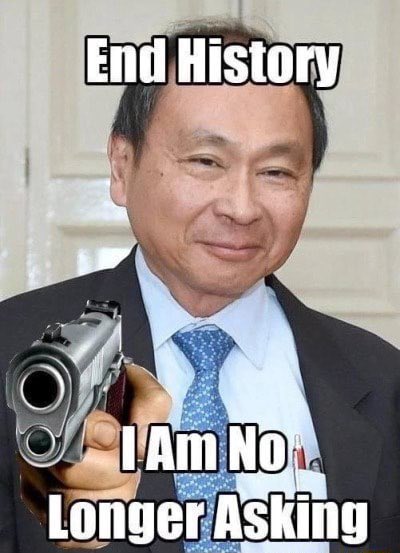

P.S. Oh, what’s that bit about overthrowing capitalism, you ask? Well that’s a discussion for another day… I’ll just leave this here for now: